廣告 ADS

Mamamamamamamama

Edited by 瞿畅 QU Chang from a chapter of her as-of-yet unfinished thesis “Feels a Lot Like Love: Love'in(g) Post-Reform China“.

Mama 媽媽

“世上只有媽媽好 Mama is the best and only

有媽的孩子想塊寶 Only mother’s children are treated as treasure

投進媽媽的懷抱 In mother’s warm embrace

幸福享不了 Happiness is endless

世上只有媽媽好 Mama is the best and only

沒媽的孩子像根草 Children without mother are like weeds

沒有媽媽的懷抱 Without mother’s warm embrace

幸福享不了 Happiness is nowhere to be found”

- “世上只有媽媽好” (“Mama is the best and only”), 1958

I am not sure whether this song was the first lullaby I learned in kindergarten. But it is the most memorable and emotionally stirring song from my childhood memories. To me, a mother’s love is always something unimaginably vast and powerful—never failing to bring me to tears when I sing, feel, describe, and imagine it.

A specific figure of motherhood, or the 媽媽 mama, has been summoned since the late Qing era in China by way of lyrics and songs, stories and poems. At the time when China’s feudal society was at the brim of collapsing, progressive intellectuals began to critically reflect upon the patriarchal system deeply embedded within it. ‘Father’ was in crisis, and ‘Mother’ was called upon to represent the new nation in a sorrowful yet resilient way. When studying at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, poet Wen Yiduo 聞一多(1899-1946) famously wrote a series of poems that likened the Chinese nation to a mother heartbroken when her children are taken away from her by bullies. The seven children, or cities, occupied by or ceded to Western (and Japanese) imperialist powers cry for their loving mother. These new concepts of both China as a ‘nation’ — in contrast to the historical Chinese cultural concept 天下 tianxia, or heavenly mandate — and woman/mother as a holy figure, are intertwined in Wen’s poetic rendering, strengthening a brand new emotional model that educated its readers on the imaginary of maternal love and one’s filial devotion to the nation. A modern and intimate, mother-child/nation-people connection begins to emerge alongside the father-son/emperor-subject relations stipulated by Confucian classics.

The emergence of the new Mother could perhaps be traced to 1903, a few years after the Qing government’s colossal defeat in the first Sino-Japanese War and a few years prior to the 1911 Revolution that marked the end of imperial China. It was the year when Jiangsu-born literati 金天翮 Jin Tianhe (1873-1947) published Women’s Bell 《女界鐘》, a volume that advocates for women’s rights and asserts women’s reproductive power to the notion of a new China.

女子者,国民之母也。欲新中国,必新女子;欲强中国,必强女子;欲文明中国,必先文明我女子。欲普救中国,必先普救我女子,无可疑也。

Women are the mother of the people. To renew China, one must renew women; to strengthen China, one must strengthen women; to civilise China, one must civilise women; to save China, one must save women — there’s no doubt.

- JIN Tianhe,《女子世界 Women’s World》, 1904

Known as the Rousseau of Chinese feminism, Jin played a pioneering role in formulating feminist theory in China, covering gender equality, freedom of marriage, and women’s rights to education and political participation, among others. One anecdote reveals another perspective to examine Jin’s feminist thoughts: after finishing the first five chapters of the roman à clef 《孽海花 A Flower in a Sinful Sea》, Jin abandoned the project, claiming that the legendary Chinese courtesan and protagonist of the novel, 賽金花 Sai Jinhua (1872-1936), marred her pen with her promiscuity.

Women’s desire, it seems, is not a consideration of the new Woman in Jin’s feminist thoughts. Who, then, are the new Women giving birth to a new China? Perhaps they are educated, romantic, and politically active women, but they also cook, clean, and raise children while having no quirks, desires, nor flaws. Women, or Mother, it turns out, is more of an idealised figure who has been invented for the sake of a new nation. In the long process of nation-building in the 20th century, Mother nevertheless opened a fertile ground, producing various voices, textures, imagery, and emotions — continuously moulded into different shapes and haunted by different values.

Mama 罵罵 (Scold!)

In 2021, the term ‘雞娃 chicken child’ was listed as one of the keywords of the year in China. The lingo refers to children and teens subject to extremely strict parenting styles, typically found in China’s middle-class or elite households. The notion of a ‘chicken child’ mirrors a well-established stereotype of Asians, especially ‘虎媽 tiger mom’ Chinese mothers. Rather than the image of the tender and loving Mother produced alongside modernising nationalist discourse, tiger moms are the representatives of ‘tough love’ expressed through scolding, beating, and critique.

Another archetype connected to the tiger mom popular in television and cinema narratives is the ‘惡婆婆 evil mother-in-law’. These are the moms who love their sons so devotedly that they ‘naturally’ form a hostile relationship with their daughter-in-laws. Such characters are portrayed as toxic, possessive, aggressive, with double-standards, and even misogynist. Audiences tend to enjoy the cathartic (爽) plot line of catfighting between mother-and-daughter-in-laws (婆媳大戰) as well as that of the more rational father saving the chicken child from the tiger mom. Maternal love, it seems, is a magic spell that can make them tender and understanding but can also turn them into tigers, witches, and villains. Mothers’ hysterical shape-shifting becomes naturalised. It doesn’t stimulate questions about their anxieties, fears, nor haunted pasts. It doesn’t bring us to think about the diaporic Asian women’s hopes for their children to lead a better lives in societies that are essentially prejudiced against their race and gender. Neither are we reminded of the fears of generations of Chinese parents who were deprived of education rights for the greater part of the 20th century and thus over-compensate for their regrets on their children, nor of the anxiety-ridden Chinese middle-class subject to fierce workplace competition and similarly project their anxieties on their children. And what about the Chinese mothers who are emotionally deprived or intensify—not to mention physically tortured (with enforced abortion and birth control)— by the one-child policy? It seems to be forgotten that there are memories, stories, and feelings which have woven Mothers into their various shapes.

Mama 抹抹 (Wipe!)

If Mother is, for a large part, imagined and constructed, what does it mean to become Mother? To inherit and perform her ‘love’? A public service advertisement from 1999, 《媽媽,洗腳》 “Let me bathe your feet, Mama”, presents one example of such a generational relay. In the ad, a young boy watches his mother bathe his grandmother’s feet. Imitating this act of love, he draws a basin of hot water and carries it clumsily to his mom, saying, “Mama, let me bathe your feet”. The campaign is a touching illustration of filial piety, one of the “中華民族傳統美德 Chinese nation’s traditional virtues”. By performing and passing on her virtue, the act of feet-bathing reveals the essence of Mother, which lies in the realm of labour. Mother’s love is always expressed through labour — through their cooking, cleaning, tidying, nagging, and crying. To love is to perform chores, to be exhausted, to become dehydrated, to lose consciousness, to change shape.

Mother’s love/labour does not only exist in the domestic realm. It spills over into public space. In China’s entertainment market, ‘養成系偶像 teenage idol culture’ has reinvented Mother for the fan economy and its flows (流量經濟和粉絲經濟). Fans of teenage idols, largely women, are able to feel longer and deeper bonds with their heroes by participating in their coming of age. They not only provide support and suggestions for the idols’ career development, but also worry about their school grades and well-being. In 2021, a teenage idol reality show produced by the streaming site iQIYI and sponsored by dairy brand Mengniu was involved in a public scandal: fans of the show purchased wholesale amounts of Mengniu’s bottled milk in order to obtain the QR code printed on the insides of its bottle caps in order to influence the voting for their favourite idols. Videos in which buckets of milk were poured into the sewer were widely shared on the internet. Mother responds to the ‘cries’ of her children, in this case, with a lactating flow of data and cash.

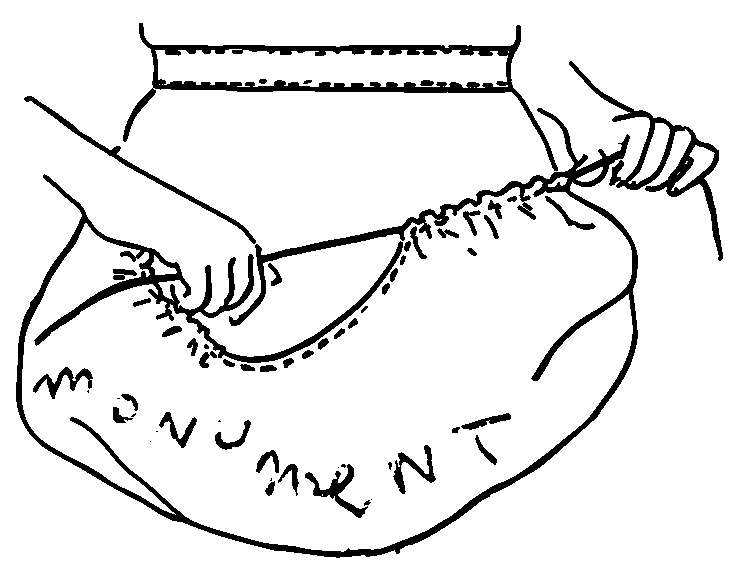

Mama 吗吗?(What?)

《小蝌蚪找媽媽 Where is Mama?》 is a 15-minute animation created in 1960 by the Shanghai Animation Film Studio. This artistic production was China’s first ink painting animation made specifically for young children learning to speak. The cartoon incorporates ink art figures as typically found in Qi Baishi’s paintings and is about a group of tadpoles in a pond searching for their mother. After having mistaken shrimp, goldfish, and other animals for their mother, they finally find their mother, the frog, who has also been eagerly searching for them. The story of tadpoles searching for a mother they have never seen is an allegory for 20th century Chinese ‘mother-child’ narratives: the children constantly imagine what their mother looks like and the love they will receive from her. Meanwhile, the Mother, who shares no resemblance to the children, is for the most part of the film out of sight.

The separation of ‘mother’ and ‘children’ not only exists in such fables; it is also experienced on a daily basis through forms of collective amnesia and reinvention between history and the present across different generations. When anthropologist Lisa Rofel conducted her research about Chinese people’s understanding and expressions of desire in the late 1990s, she noticed what she described as a form of ‘structural forgetting’ that has engendered modern-day consumer identity in China: children have to forget and denounce their mothers’ Communist Cultural Revolution pasts to embrace the new, carefree, neoliberal reality, while mothers themselves have to forget their own histories so that they may be accepted as integral parts of the reformed China and its newly written historical narratives. In contemporary China, it is perhaps precisely such an amnesia that provides room for the endless symbolisation of Mother and, in turn, shapes individuals into Mothers unable to share inherited knowledge or memory with their children. What remains are the language and performance of love. Mama can be found in melodrama, in domestic worker agencies, in restaurants and supermarkets. You may cry and eat and burp, and you may get tucked in, but you still don’t know where Mama is.

評價 Reviews

Your e-mail address will not be published

* 必填 Required fields